The Curiosity Gym

Three Essential Books That Will Build Your Curiosity Muscle

My internal drive of curiosity began first with a drive for continuous improvement. As the oldest of five children, I regularly felt I needed to be a “good example” to those around me, even from an early age.

Specifically, what I realized about myself was an innate ability to visualize the future. Every night I would lay in bed and visualize my entire day — the absolute best version of it. Sometimes, like in the case when the theme park my family had season tickets to was closed without our knowledge, my eight-year-old inward emotions would explode in outward frustration. There wasn’t a lot of health in setting myself up for ongoing disappointment.

This is where I discovered a healthier version of continuous improvement — curiosity. It’s an ongoing battle, but I believe a mindset shift from unreasonably high expectations and continuous improvement brought about an ability to lead over time. It was the mind shift from ambition (I can see the goal clearly and will do anything to achieve my dreams) to aspiration (I have a generally high goal, but the journey is unclear and I’ll discover it along the way).

To mentally survive, I had to let go and get curious.

There are a thousand books on this topic to grow the “Curiosity Muscle,” but I think the next three are some of the best.

The 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership by Diana Chapman, Jim Dethmer, and Kaley Klemp

The 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership was introduced to me during my time at altMBA. This book perfectly describes my aspirational goal regarding my personal and leadership philosophy. I pick it up almost weekly to reflect on these commitments, from taking full responsibility to creating win-for-all solutions and encouraging leaders to question their assumptions and beliefs constantly.

The “above and below the line” thinking process fosters curiosity, pushing leaders to explore new perspectives and understandings.

Leading “above the line” is associated with asking questions like:

"What can I do to change this situation?"

"How can I contribute to a better outcome?"

It reflects an open, curious, and constructive approach to challenges.

On the other hand, the “below the line” mentality is marked by reactivity, blame, and victimhood. When we are below the line, we feel powerless and blame others or external factors for trials and tribulations. Typical questions arising from a below-the-line mindset include:

"Whose fault is this?"

"Why does this always happen to me?"

We’ve all been there.

Clear Thinking by Shane Parrish

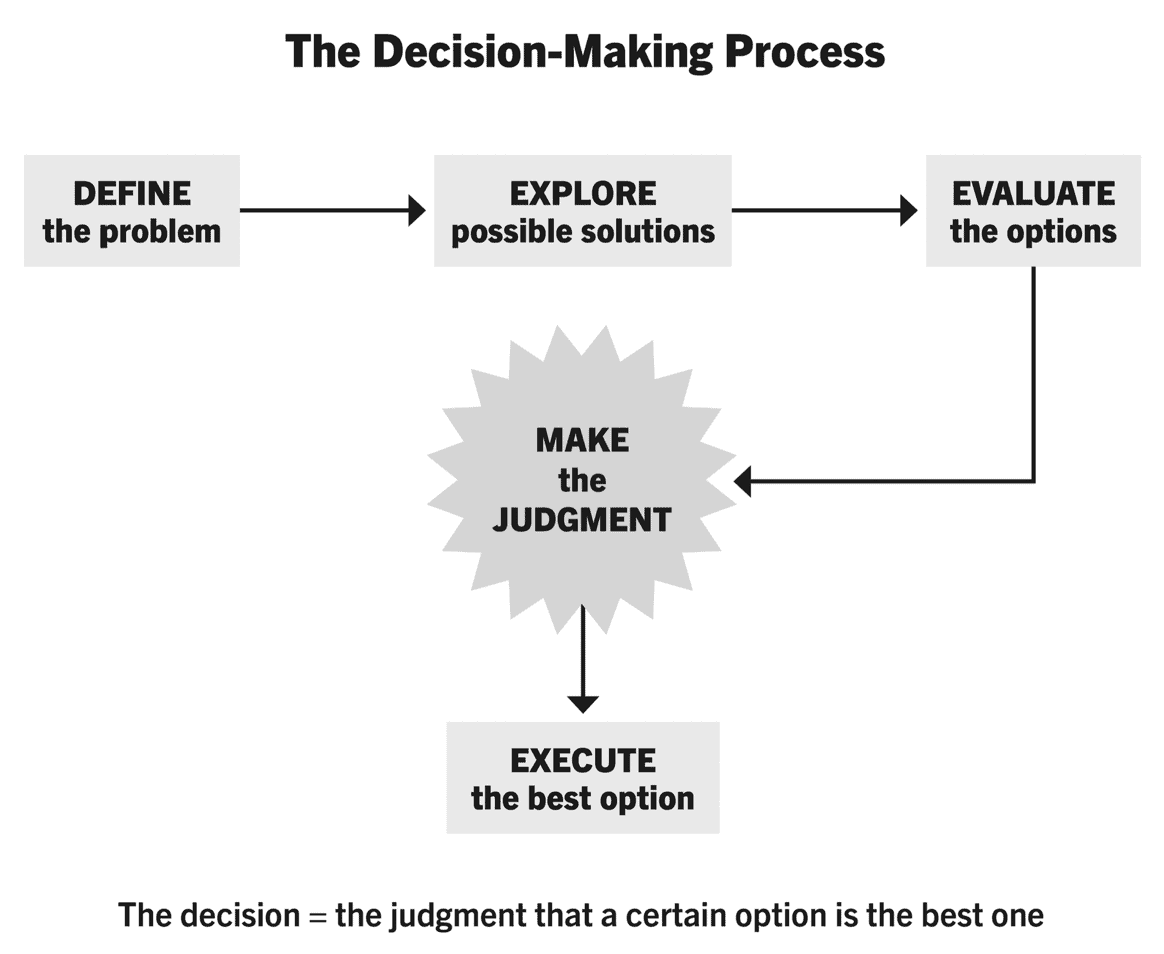

In Clear Thinking, Shane Parrish (who I have written about with the Shane Parrish Starter Guide here) delves into the art and science of rational decision-making. Shane is known for his work on the Farnam Street blog, which combines many tools and strategies to enhance cognitive abilities.

Parrish’s emphasis on mental models – frameworks that help understand the world – is particularly relevant for nurturing curiosity.

“If you’re like me, no one ever taught you how to think or make decisions,” writes Shane. “There’s no class called Clear Thinking 101 in school. Everyone seems to expect you to know how to do it or learn how on your own. As it turns out, though, learning about thinking—thinking clearly—is surprisingly hard.”

This ability, however, is essential to curiosity. Curiosity does not mean unrestrained. I think it’s a search for clarity and should be able to help you make better decisions.

Shane introduces and explains various models and invites readers to look at problems from multiple angles. This multidimensional approach improves problem-solving skills and sparks a sense of wonder and inquiry.

“The overarching message of this book is that there are invisible instincts that conspire against good judgment,” he says. “Your defaults encourage you to react without reasoning—to live unconsciously rather than deliberately.”

One of my favorite pieces of the book is the frameworks that help you determine and decide when you should get more curious and learn more or stop adding data and make a decision. This is the ASAP vs. ALAP principle.

ASAP Principle:

“If the cost to undo the decision is low, make it as soon as possible.”

ALAP Principle:

“If the cost to undo a decision is high, make it as late as possible.”

The Opposable Mind: How Successful Leaders Win Through Integrative Thinking How Successful Leaders Win Through Integrative Thinking by Roger Martin

The Opposable Mind presents the ultimate case for integrative thinking, a cognitive process that involves synthesizing conflicting ideas to create innovative solutions. Roger Martin argues that successful leaders can hold two diametrically opposed ideas in their minds and, rather than choosing one at the expense of the other, use the tension between them to generate a creative resolution.

Integrating diverse perspectives necessitates a deep curiosity about how different ideas and viewpoints can coexist and complement each other. Martin’s exploration of how notable leaders have applied integrative thinking in real-world scenarios provides practical insights into how curiosity can lead to groundbreaking ideas and solutions.

“When responding to problems or challenges, leaders work through four steps,” writes Roger Martin. “Those who are conventional thinkers seek simplicity along the way and are often forced to make unattractive trade-offs. By contrast, integrative thinkers welcome complexity—even if it means repeating one or more steps—allowing them to craft innovative solutions.”

Thanks for reading,

Tim, this week's post is just packed with value and useful info. First of all, your explanation of how curiosity for you arose as a coping mechanism is fascinating. I'd never considered it that way but upon reflection I think a measure of this was true for me too. That curiosity could be an intelligent way to manage stress and adversity is beautiful. The 15 commitments of conscious leadership is one of the most potent frameworks of leadership focus I've seen. I resonate very strongly with the competencies curated by the authors for this model. And finally for me, the explanation of the ASAP and ALAP approach so well articulates something I've intuitively done in my life, but no have a simple and clear way to explain. Thanks as usual for the fine essay.